Brazil's aquaculture industry is primarily known for tilapia production; however, the country also farms other species such as shrimp and a wide variety of native fish from the Amazon basin and the central marshland areas in the Midwest region. One of these species is Arapaima gigas, known as paiche in Peru and pirarucu in Brazil. It is one of the largest freshwater fish species in South America, with a unique characteristic—it is an obligate air breather.

Breeding challenges

Despite the significant interest in pirarucu, many challenges remain to make it a profitable, commercially viable species, particularly in reproduction. As an ancient species, its reproductive system is entirely different from that of other fish.

“Species like tilapia, for example, which is the most commonly bred in captivity in Brazil, can reproduce in less than a year,” explained Alexandre Caetano, a researcher at EMBRAPA. “But native species, such as pirarucu and tambaqui (Colossoma macropomum), do not reproduce as easily in captivity and require years to reach reproductive maturity.”

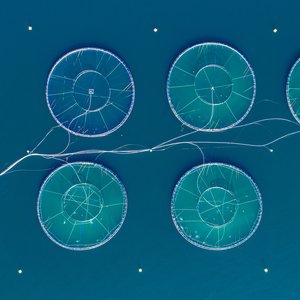

For pirarucu, no established protocol for hormonal induction exists, and due to their territorial nature, each pair must be housed separately in individual tanks. “In the wild, males are territorial. Therefore, each pair must occupy a separate tank, which requires significant space. If you place two pairs in one tank, they will fight for territory. Imagine two 250-kilogram fish fighting,” noted Caetano.

Another reproductive challenge involves egg release. In most fish species, females spawn all their eggs at once, and the males fertilize them simultaneously. In contrast, pirarucu females release their eggs in batches, which are fertilized gradually.

Credits: Simone Oliveira Yokoyama

Market challenges

A further obstacle is price volatility in the market, as farmed pirarucu competes with wild-caught fish. “Under normal conditions, fishing can supply the market at competitive prices. For farmers, in a good fishing year, market prices can fall below production costs,” Caetano explained.

On the positive side, pirarucu can grow up to 10 kilograms within its first year of life. “There’s no other fish species with comparable growth,” Caetano added.

Some producers have managed to address market and production challenges. For instance, some now produce captive pirarucu fry, while others have mitigated price fluctuations by operating near consumer markets. Caetano highlighted an example of a producer near Jundiaí, São Paulo, who, although unable to breed pirarucu on-site, sources fry from another region. “This producer faces an added challenge since the fish cannot tolerate the region’s winter cold. As a result, everything must be done in greenhouses. However, they deliver a high-quality product to a well-valued market in São Paulo, where there is demand from haute cuisine, hotels, and other premium outlets. It’s an interesting niche. Regardless of fishing activity, they remain competitive with a very fresh product,” said Caetano.

In contrast, producers in Brazil’s Northern Region face more significant challenges due to greater market fluctuations.

New genomic tool

Embrapa Genetic Resources and Biotechnology has developed a genomic solution, ArapaimaPLUS, to support the management, use, selection, and genetic improvement of pirarucu breeding stocks.

According to Caetano, one of the developers of ArapaimaPLUS, the tool is essentially a genomic test designed for paternity analysis, kinship verification, individual identification, and genetic variability assessment. It can be applied to the genealogical management of breeding stocks in aquaculture operations focused on pirarucu reproduction.

“The solution offers all the basic applications of other tools—such as genetic management and breeder analysis—but also has the potential to support traceability processes and the monitoring of wild populations and fishery products,” said Caetano.

ArapaimaPLUS is the sixth genomic solution developed under the AquaPLUS platform, which also includes technologies for tilapia, tambaqui, shrimp, and trout. Embrapa is currently validating platforms for other fish, including pirapitinga (Piaractus brachypomus) and pacu (Piaractus mesopotamicus). “We already see demand for other species, such as matrinxã (Brycon cephalus) and dourado (Salminus brasiliensis). Our goal is to develop technologies for all species of interest to Brazilian aquaculture. Supporting producers is our mission,” concluded Caetano.

The ArapaimaPLUS project was funded by the Federal District Research Support Foundation (FAP-DF) and involved collaboration with researchers like Michel Yamagishi from the Multiuser Laboratory of Bioinformatics at Embrapa Digital Agriculture. Validation of the tool was part of Aline Campelo’s master’s thesis at the University of Brasília.